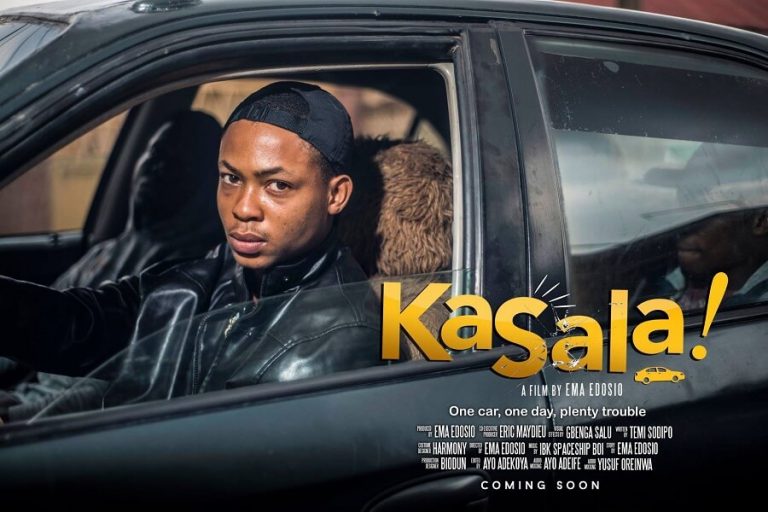

Ema Edosio’s Kasala is Disturbingly Original

By Dare Dan

Kasala— which is pidgin slang for trouble —is a fast-paced comic in its most unconventional form. We know stand-up comedy, TV comedy, comics of short skits on the internet, satirical writings, even radio comedy; but comedy, rooted in realism, is not something we often come across on Nigerian screens.

To say that everyday life in Lagos can sometimes be funny and exhilarating is saying the obvious – and artists of various specialities have, over years, tried to organically adapt these tragicomic events in their works. This has not always been quite easy. But to an intent onlooker, and a quite creative mind, who Ema Edosio has proved herself to be in this film, Lagos can be hilarious still, and its hilarity can very much be employed cinematically.

These every-day scenarios are, of course, not preplanned to make anyone laugh; they are events springing from the core of human nature when it’s been subjected to the excruciating or very unfavourable condition. It takes a careful listener to tap into the depth of ensuing conflicts without sentiments; perhaps, with a little exaggeration or staginess, achieve a result so realistic, so true and so funny.

Ours are cohabitations of some of the highest numbers of people in a given space, numbers shooting far beyond available basic social amenities. With the shortage of basic social services comes various invented or improvised means of livelihood. These other means are what we generally refer to as Hustle.

The whole drama is around a car—bought, in the buyer’s house, but not fully paid for—and four exuberant lads in a typical overcrowded neighbourhood in Lagos Mainland. All the four boys are hustlers of different grades. (One can’t help but notice the director’s stunts with the camera in her depiction of details, her razor-sharp sensitivity to what life is like in these neighbourhoods from the very first shot. How on earth can you tell someone’s disorientation to the point of insanity with a camera? Well, see Kasala).

It is a bad morning from the word go for every one of the lads (TJ, Abraham and the two others) in their respective abodes. The morning is especially bad for TJ, whose money is stolen and thinks the day will not go for him as planned—until he finds his uncle’s car keys. Blessing in disguise, he thinks. He pounces on the car, ignites it and drives to a party with his friends.

Uncle Taju, a butcher, had saved all his earnings to buy the car from a certain ruthless chief (played by the renowned Jide Kosoko), who, with his thugs, is determined to make life a living hell for Uncle Taju if he doesn’t pay up for the car or return it.

These four guys can’t be any more real and fun to watch, carrying out their roles like the guys next door. I haven’t met any of them, but I can bet I know them; every such neighbourhood knows them.

It is blessing indeed until they have an accident with the car. It then boils down to putting their hustling prowess in full play; prove what they are worth when it comes to surviving the times; raise money to fix the car before the arrival of uncle Taju. The film from then on plunges into a whirlwind of puerile events.

If to pick on any reason why this film is not a classic, it would be in the storytelling and not the directing or production in general. The story, which is one-directional—no turn of events, that is— tends to be interested in making its audience laugh and laugh only. Even in the face of grave situations. For example, despite having his father on a dying bed, one of the lads still goes ahead to steal from him to salvage the car, to buttress friendship. This singular act of heartlessness is one too extreme and morally debasing. In attempting to appraise the idea of brotherhood, the film has gone ahead to quash family bonds. And then there is a situation of a drug addict doubling as a mechanic. With such cases, one would expect a story that wouldn’t just reel us through a laughing spree, but, somehow, creatively incorporate these events into its telling. This is how classics like Sex, Okra and Salted Butter by Mahamat-Seleh Haroun are made.

You may argue that the film is loud with a lot of curse words, but that’s exactly what we are in this society. The film is disturbingly original. Edosio seems to be out targeting a feat of originality rarely obtainable in the Nigerian film industry; no doctoring or staging or playing around a storyline that is more or less unrealistic. No melodrama.